++++

++++

Stephanie Pearce

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2013 edition "Chavismo After Chávez: What Was Created? What Remains?"

Countries in the “developing world” have, since the end of formal

colonialism, seen their ability to act autonomously systematically

constrained by a variety of factors. These include, but are not limited

to, macroeconomic policy conditions attached to World Bank and IMF

loans, poor terms of trade with the Global North, lack of effective

agency in international organizations, and the actions of multinational

corporations operating in their territory.

Venezuela’s regionally oriented foreign policy during the Chávez era

counteracted each of these dynamics, and in doing so opened up

autonomous policy space for other states in Latin America and the

Caribbean. The concrete achievements of a number of mechanisms,

including counter-trading and credit provision within the PetroCaribe

framework, and the recent establishment of a virtual regional currency,

the SUCRE, all played a part in this process.

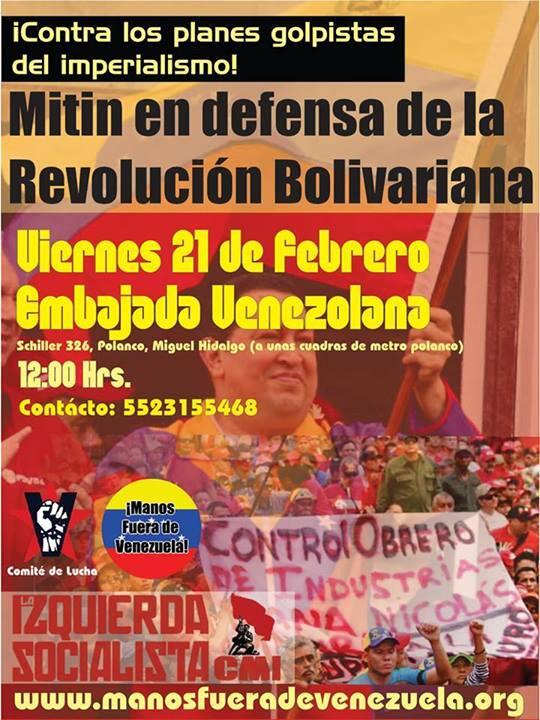

PHOTO BY MICHAEL FOX

PHOTO BY MICHAEL FOX

The first crucial action undertaken by Hugo Chávez as Venezuelan

President in protecting regional economies was to vociferously oppose

the proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) at the third summit

of the Americas, held in Quebec in 2000. The proposal represented the

perfect consolidation of U.S. economic power, and was designed, in the

words of General Colin Powell, to “guarantee control for North American

businesses...over the entire hemisphere.”1 After Chávez

voiced concerns, the Mercosur countries followed suit, stopping the FTAA

conclusively at the subsequent Mar del Plata summit in 2005. If the

FTAA had gone ahead, it would have resulted in the substantial economic

subordination of Latin America to U.S. corporate interests. Agricultural

sectors in particular would have suffered from an influx of low-cost

subsidized U.S. products. In addition, areas of the public sphere that

had previously avoided commoditization or privatization would have been

fair game for trans-national corporations. Under the FTAA, Amanothep

Zambrano, ALBA Executive Secretary, told me last August that states

would not have been able to “lead any aspect of economic policy, and

therefore their political capacity to solve social problems” would have

been heavily constrained.

Their shared opposition to these proposals encouraged Cuba and

Venezuela to form an alternative regional integration framework, the

Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA) in 2004. This

quickly matured from a bilateral socio-centric cooperation agreement to a

nascent regional bloc, or alliance, with the addition of

Bolivia in 2006. Bolivia’s newly elected president, Evo Morales, brought

with him the idea of a “Peoples Trade Treaty” (TCP), which extended the

ALBA’s self-identified principles of solidarity, complementarity

between economies, and respect for sovereignty, into a 23-point

agreement that systematically opposed the tenets of orthodox free trade

agreements. The TCP opened the possibility of pursuing economic policies

outside of the market fundamentalist approach of the neoliberal era,

for example by stating that people’s right to access healthcare should

be prioritized above protecting pharmaceuticals’ corporate

profitability. In the following three years, membership of the ALBA-TCP

grew to nine countries encompassing much of Central and South America as

well as the Caribbean.

During this time, the Venezuelan government also constructed

PetroCaribe, a framework designed to facilitate the supply of its oil

products to neighboring Caribbean states under preferential conditions,

which at the time of writing had 18 members. Through these two channels

the Venezuelan government has opened up autonomous policy space in the

region, to some extent overcoming the constraints identified above.

Venezuela has, largely through ALBA and PetroCaribe, become an important

source of funding in the region. Oil supply agreements, signed between

Venezuela and several members of both frameworks, permit countries to

defer payment on set portions of their oil bill and use the capital

obtained for government spending. Crucially this capital is obtained

without the macroeconomic conditionality and policy prescriptions

associated with World Bank or IMF loans.

PetroCaribe agreements, for

example, state that “member nations of the group are allowed to defer

payment of 60% of their oil bills to Venezuela for 25 years, at 1%

interest, in addition to a 90-day grace period on all payments, and a

two year initial grace period on the credit facility.”2

PHOTO BY DARIO AZZELLINI

PHOTO BY DARIO AZZELLINI

This credit facility offers an alternative to IFI loans, while

maintaining small Caribbean nations’ ability for autonomous decision

making, which is considered critical in the post-colonial context.

Specifically, credit provision has enabled Jamaica and Antigua to delay

recourse to IMF loans, and put them in a better negotiating position so,

I was told in August 2011 by Norman Girvan, former Secretary General of

the Association of Caribbean States, “they were able to make an easier

deal.” Venezuela, under the current administration, has also purchased

billions of dollars’ worth of bonds issued by the Argentine government,

enabling the country’s early exit from all of its IMF debts and

associated policy prescriptions.

As a result of this mechanism, PetroCaribe funding to the Caribbean

now exceeds both EU and U.S. aid by a wide margin, with only remittances

from the Caribbean diaspora exceeding it in funding to the signatory

states.3 For Dominica, Venezuela is now the “single largest

creditor...surpassing traditional sources of credit such as regional

development banks and the IMF.” Venezuela is owed 27.7% of the country’s

total debt, which grew 12.6% in 2011 alone, to $8.8 billion.4

Such figures inevitably raise concerns that the agreement is increasing

debt levels in the region and developing dependence on Venezuelan

largesse. Barbados’s Prime Minister, Owen Arthur, has stated that his

country would not join because he “would not permit the present

generation of Barbadians to consume oil now to be paid for by succeeding

generations of Barbadians.”5 However, the deferred portion

of the bill does not constitute debt in the orthodox sense, as it is

kept by the Caribbean partners and can be spent as capital towards any

project deemed socio-productive, or saved to accrue interest to offset

the bill, as has been the case in Guyana. The domestic opposition sees

the PetroCaribe scheme as Chávez “giving away” oil irresponsibly.

However, the amount is relatively small and sustainable. Supply to

PetroCaribe members, including Cuba, peaked in 2009 at an average of

196.4 thousand barrels daily, which constituted only 7% of total

Venezuelan oil exports that year, and operates under market prices in

accordance with Venezuela’s OPEC membership.6

Due to a high level of dependence on imports, Venezuela has also been

uniquely able to position itself as a regional alternative to North

American and European markets. This dynamic has, again, been apparent

within both ALBA-TCP and PetroCaribe. In 2008, the PetroCaribe framework

was augmented with a “compensatory exchange mechanism” via which oil

bills from Venezuela could be offset by the export of domestically

produced goods and services. The Venezuelan market is particularly

important for Caribbean countries who suffer from poor terms of trade

with the North due to dependence on primary commodity exports, the

continued use of tariff and non-tariff barriers by developed nations,

and the erosion of colonial trade preferences. For example, up to 90% of

Guyanese rice exports per annum were going to EU countries when, in

2000, the Overseas Territories (OCT) loophole was closed, resulting, I

was told by the Guyanese Ambassador to Venezuela, in a “50-60%” drop in

prices. When the compensation mechanism was announced, the

then-president of Guyana, Jagdeo Bharrat, actively sought a better deal

with Venezuela through the PetroCaribe framework. The resultant export

of both rice and unprocessed paddy has seen Venezuela become the single

largest importer of Guyanese rice, replacing Portugal.7

In the case of ALBA countries, a strategic reorientation towards

intra-regional trade, and particularly export to Venezuela, has reduced

dependence on the United States and subsequently its ability to

constrain autonomous action. For example, when Bolivia expelled the U.S.

ambassador in 2008 following his alleged involvement in separatist

actions in the Santa Cruz Department, Washington retaliated by excluding

Bolivia from the Andean Trade Promotion and Drug Eradication Agreement

(ATPDEA). Bolivia lost its U.S. tariff advantages, which was a

particularly painful blow to its textile industry. Chávez immediately

offered them a market under “the same or better conditions” that Bolivia

had enjoyed with the United States. As a result, says the Bolivian

Ambassador to Venezuela, in 2010 Venezuela “imported almost 50 million

dollars in textiles alone, or nearly double that which [Bolivia] used to

export to the USA” annually.

The purchase agreement was supported by initiatives by both

governments to facilitate small and medium sized businesses’ entry into

the regional market. A fund was established in the Bank of ALBA to

provide short-term interest-free credit to Venezuelan importers in order

to purchase Bolivian textiles, paired with a fund in the Bolivian

national development bank to provide small textile producers credit to

purchase raw materials. This agreement therefore not only minimized the

impact that U.S. market sanctions could have over autonomous decision

making by the Bolivian government, but also created direct relations

between regional producers and consumers.

These patterns are part of a wider renewed focus on South-South

trade, both within the region and with extra-hemispheric partners.

However, the United States remains the region’s single most important

trading partner. The objective is not to be “anti-American,” rather to

reduce the U.S. ability to exert controlling influence over its Latin

American and Caribbean neighbors by creating alternatives to the dollar

in international trade. One way in which this was achieved was through

the PetroCaribe mechanism and similar counter-purchase agreements with

other regional allies. As direct non-market transactions, they

circumvented the use of the dollar, thereby avoiding its automatic

privileging in international trade, and avoiding the transaction costs

associated with its use.

This concept was extended by the ALBA’s virtual common currency, the

Unified Regional System for Economic Compensation (SUCRE). The SUCRE is

essentially a series of clearing accounts between Cuba, Bolivia,

Venezuela, and Ecuador that allow the countries to trade freely without

transaction costs. Accounts are balanced every six months with one hard

currency transfer. The value of trade conducted via the SUCRE in its

first year of operations, 2010, was just over $8 million. It grew

exponentially, to almost 100 times that the following year

($172,905,344).8 Though the SUCRE’s value was originally set

against the dollar ($1 to XSU1.25), and it is typically used as the

convertible currency to make balancing payments, in the long term the

intention is to no longer use the dollar at all. The direct and

deliberate countering of U.S. economic hegemony that the SUCRE

represents has been of particular importance to Ecuador, whose

macroeconomic policy options have been constrained by a prior

administration’s decision to dollarize the economy in 2001. In fact, the

mechanism was largely designed by Ecuadoran economists, and of the $170

million traded in 2011, $140 million was for Venezuelan purchases from

Ecuador (mainly tuna).9

As we have seen, Chávez’s time in office saw an unequivocal

reassertion of the state as economic actor throughout the region. This

dynamic was particularly felt in the crucial energy sector. In

Venezuela, governmental control of the state oil industry was

consolidated, while both Bolivia and Argentina nationalized hydrocarbons

with investment and technical assistance from Petroleos de Venezuela

(PDVSA), via agreements with YPFB and Enarsa, state owned gas and oil

companies in Bolivia and Argentina respectively. Even in centrist or

center-right Caribbean nations, Venezuelan investment has enabled

state-owned oil companies and agencies to supply oil products directly

to their population, “to effectively intervene in their markets to

minimize retail prices” in the energy sector which had previously been

“dominated by foreign companies.”10

Where state energy companies or agencies did not exist prior to

PetroCaribe, they have been formed to facilitate the direct import of

oil products from PDVSA. These can take the form of joint ventures with

the PDVSA subsidiary PDV Caribe. Venezuelan credit and grants have also

been used to fund improvements in energy infrastructure; that is namely

the capacity of the member countries to store and refine oil, and in

turn to generate and distribute energy. Central to this scheme has been

investment in the Cienfuegos refinery in Cuba and at the Kingston

refinery which now almost exclusively refines Venezuelan crude. The

refinery is run by Petrojam Ltd, a mixed state enterprise in which

Jamaica Oil Company owns a 51% stake and PDV Caribe 49%. This

reassertion of state control over energy resources is seen as a

fundamental facet of PetroCaribe’s “new oil geopolitics…at the services

of our peoples not at the service of imperialism and big capital.”11

The right and power of multinationals to dictate domestic policy has

been systematically undermined, both through a reassertion of the state

as economic actor and in the tenets of the TCP which we briefly touched

on earlier. This offers a stark contrast to the World Trade

Organization’s policies such as Trade Related Intellectual Property

Rights (TRIPs), which consistently privilege corporate interests, and/or

offer beneficial “loopholes” for developed nations. This has been

possible through the creation of new regional forums in Latin America

and the Caribbean, in which members’ interests are not subordinate to

those of more powerful nations. For example, in the TCP, economic

asymmetries between members are recognised and therefore tariff

reductions do not have to be reciprocal, disregarding the “most favored

nation” principle. In addition, ALBA has no supranationality; it is best

described as a framework for cooperation rather than an integration

body in the orthodox sense. All programs and agreements are optional,

flexible, and voluntary, thereby protecting the national autonomy of

members.

Though statist in its organization, ALBA facilitates continual

dialogue through presidential and ministerial summits, which have also

been attended by international observers. Non-member countries are also

represented in the council for social movements, whose proponents

include groups such as the Brazilian Landless Workers’ Movement. ALBA

proved to be the first in a series of new regional spaces, catalysed by

massive rejection of the FTAA proposal—a rejection led by Chávez—and

culminating in the formation of the Community of Latin American and

Caribbean States (CELAC), which was put together as an alternative to

the Organization of American States (OAS), and includes all the

countries of the Americas except the United States and Canada. In this

way, lessened economic dependence has resulted in increased diplomatic

autonomy from the United States.

There are those who argue that Venezuelan projects in the region

created new constraints, replaced one set of dependencies with another.

But this is not the case. Though he was a catalyst for and investor in

regional development, Chávez avoided constructing a position of power or

privilege for Venezuela. This is evident in the lack of conditionality

attached to credit mechanisms and the fact that the controlling stake of

each mixed state enterprise was maintained by the partner country.

Though oil wealth put Chávez in a unique position to invest in regional

projects, these were not unilaterally devised or constructed; the TCP

came from Bolivia, SUCRE is an Ecuadoran concept, and of course ALBA

social programs were exported from Cuba. However, these ideas were made a

reality by the capacity for rapid implementation that oil largesse

afforded. Such apparently altruistic actions led many to question

Chávez’s motives. It is important to point out that these frameworks and

counter-purchase agreements have also helped reduce Venezuela’s

dependence on the United States as a market and refining destination for

oil. The volume of Venezuelan oil exported to the United States

decreased from 1,500,000 barrels per day in 2008, to 1,166,000 bpd in

2011, a drop of 334,000 barrels per day. This can, in part, be

attributed to the diversification of markets in Latin America (190 bpd

to PetroCaribe, plus supply agreements with Argentina among others).

This is in addition to securing crucial imports without financial

outlay, specifically agricultural commodities, which are often then

provided to the Venezuelan population at low cost through state owned

agencies such as the supermarket chain Mercal.

*

Under the last ten years of Hugo Chávez’s Presidency, Venezuela’s

foreign policies resulted in an opening up of autonomous policy space in

Latin America and the Caribbean. What was begun in 2004 with the

rejection of the proposed FTAA continued into the post-crisis

conjuncture, when Chávez was instrumental in creating a new regional

financial architecture to limit the power exerted by Washington-based

IFIs. PetroCaribe credit provided funds for capital expenditure, without

imposing macroeconomic conditionality. In addition, guaranteed oil

supplies allowed the small and energy dependent nations that made up its

membership to move beyond reactive policies and look to longer term

socio-productive investment.

Venezuela’s concurrent strategy of sourcing imports from the region

offered primary-commodity-dependent economies some opportunity to

diversify their markets and baskets, with better terms of trade than

offered by the United States or ex-colonial metropoles in Europe. Chávez

also took the bite out of attempted control via market sanctions, as

was clearly demonstrated in the Bolivian example.

These regional imports often took the form of non-market exchanges

and counter-purchase agreements within PetroCaribe, ALBA, and beyond.

Combined, they arguably represented a strategic de-linking from

international trade and finance systems, specifically from the U.S.

dollar. As such, these frameworks have lessened both the dependence on,

and influence of, the United States in the region, protecting countries’

ability to act autonomously and not follow the dictates of Washington.

Chávez effectively undermined U.S. economic power by offering

alternatives to the hegemony of the dollar, with the SUCRE in particular

offering a concerted challenge. Lessened economic dependence in turn

allowed for greater diplomatic autonomy from Washington, demonstrated in

its strategic exclusion from the newly formed CELAC. The various new

regional initiatives provide space to build development strategies and

devise economic policies, beyond the constraints of “market-friendly”

logic. This allows for a reassertion of the state as an economic actor

and service provider, within a culture of regional cooperation. Though

the Venezuelan state is not operating outside of capitalism per se, from

the initial rejection of the proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas

in 2001 the Chávez government demonstrated that there are alternatives

beyond the policy prescriptions of the neoliberal era, and what’s more,

facilitated their use throughout the region to mutually beneficial ends.

1. Colin Powell cited in Katharine Ainger, “Trading Away the Americas,” New Internationalist, Issue 351, November 1, 2002, available at newint.org

2. “Venezuela: Two Countries Hold Out Against Cheap Loans and Barters,” Countertrade & Offset, 26:15 (2008)7

3. Sir Ronald Sanders, “The Chavez Effect: A life belt for the Caribbean,” Kaieteur news online, July 27, 2008, available at kaieteurnewsonline.com

4. Andrés Rojas Jiménez “Deuda dominicana con PDVSA aumentó durante 201,” El Nacional, February 16, 2012, available at elnacional.com

5. Wendell Mottley, Trinidad and Tobago’s Industrial Policy 1959-2008 Kingston. (Randle, 2008) 157.

6. This data, and all data not otherwise cited, elaborated from PDVSA annual reports, 2009-2011.

7. Guyana Rice Development Board, “Guyana Rice Development Board Annual Report 2010,” 2011.

8. Consejo Monetario Regional del SUCRE, “SUCRE Informe de Gestión 2011,” 2012.

9. Ibid

10. Curtis Williams, “Venezuela Urged to Fast-track Petrocaribe Initiative,” Oil and Gas Journal, 102 (2004):26.

11. Hugo Chávez Frías, Petrocaribe, Towards A New Order in Our America, (Colecciones Discursos, Ministerio de Poder Popular para Comunicación.)

Stephanie Pearce is a doctoral candidate at the School of

Politics & International Relations, Queen Mary College, University

of London. Her research focuses on the role of countertrade in

Venezuela’s “Bolivarian Revolution.”

Read the rest of NACLA's Summer 2013 issue: "Chavismo After Chávez: What Was Created? What Remains?"